My Media Is Always Corectly

Saturday, 30 July 2011

Iwasaki Yatarō (MITSUBISHI)

Iwasaki was born in a provincial farming family in Aki, Tosa province (now Kōchi Prefecture), the great grandson of a man who had sold his family's samurai status in obligation of debts. The son of a provincial farmer, Iwasaki began his career as an employee of the Tosa clan. The clan had business interests in many parts of Japan, which whetted Iwasaki's ambition.

Iwasaki left for Edo (now Tokyo) aged nineteen in search of an education to further his ambitions. The serious injury of his father in a dispute with the village headman brought him home from Edo a year later and briefly interrupted his studies. When the local magistrate refused to hear his case, Iwasaki accused him of corruption and was sent to prison for seven months. After his release, Iwasaki was without a job for a time before finding work as a village school teacher.

Returning to Edo, he socialised with political activists and studied under the reformist Yoshida Toyo, who influenced him with ideas of opening and developing the then-closed nation through industry and foreign trade. Soon, through Yoshida, he found work as a clerk for the Tosa government, and bought back the family's samurai status with the wages he saved. He was later promoted to the top position at the Tosa clan's trading office in Nagasaki, responsible for trading camphor oil and paper to buy ships, weapons, and ammunition.

Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, which forced the disbandment of the shogunate's business interests, Iwasaki travelled to Osaka and leased the trading rights for the Tosa clan's Tsukumo Trading Company. The company changed its name to Mitsubishi in 1873.

"" MITSUBISHI ""

The company adopted the name Mitsubishi in March 1870, when Yatarō officially became president. The name Mitsubishi is a compound of mitsu ("three") and hishi (literally, "water chestnut", often used in Japanese to denote a diamond or rhombus). Its emblem was a combination of the Iwasaki family crest and the oak-leaf crest of the Yamanouchi family, who were leaders of the Tosa clan which controlled the part of Shikoku where Yatarō was born.

Mitsubishi was later almost on its feet when the Formosan Incident occurred. Fifty-four Japanese fishermen died on the island of Formosa (currently known as Taiwan) but the Empire of the Great Qing government did not take responsibility. Yatarō's company was initially blamed but the situation eventually improved and Yatarō even won the right to operate the government ships and the transportation of men and material. The company began to flourish again.

Yatarō was dutiful to the new Japanese government, as well as to his company. Mitsubishi provided the ships that carried Japanese troops to Taiwan. This earned him more ships and a large annual subsidy from the government. He agreed, in turn, to carry mail and other government supplies. With government support, he was able to purchase more ships and increase Mitsubishi's shipping lines, which helped him drive two large foreign shipping companies out of the lucrative Shanghai route through the Mitsubishi Transportation Company which Yatarō founded. Later the now-giant shipping company also carried troops to put down a rebellion in Kyushu. Yatarō taught his subordinates to "worship the passengers" because they were sources of revenue.

Subsequently he invested in mining, ship repair and finance. In 1884 he took a lease on the Nagasaki Shipyard and renamed it Nagasaki Shipyard & Machinery Works, allowing the company to undertake shipbuilding on a large scale.

In 1885, Yatarō lost control of his shipping company in the wake of a political struggle that had buffeted Japan's marine transport industry. The company merged with a rival and became Nippon Yusen (NYK Line), which would return to the ranks of the Mitsubishi companies years later.

Though Yatarō had lost his shipping company, he established other businesses (in banking, mining, newspapers and marine insurance) which formed the foundation for the Mitsubishi organization. His wealth exceeded one million yen. Yatarō was so confident of his power that he could allow himself to participate in many businesses. Mitsubishi Kawase-ten, for example, was a financial exchange house that also engaged in warehousing business. It was the forerunner of today's Mitsubishi Bank and Mitsubishi Warehouse & Transportation. Yatarō had also purchased a coal mine and a copper mine and had leased a Nagasaki shipyard from the government. He had participated in establishing the insurance company that now is Tokyo Marine and Fire. He even headed up the school that became the Tokyo University of Mercantile Marine.

Iwasaki Yatarō was a visionary businessman. He often gave dinners in the company of dignitaries, spending a huge amount of money on these occasions but he also making many friends who later helped him by doing many favors.

Yatarō, however, did not lead the Mitsubishi organization in its new phase of growth. He died of stomach cancer aged 50, and was succeeded as the head of the family business first by his brother, and later his son, Hisaya

Enzo Ferrari (FERRARI CAR'S)

Enzo Anselmo Ferrari (pronounced [ˈɛntso anˈsɛlmo ferˈrari]) (February 18, 1898[1] – August 14, 1988) Cavaliere di Gran Croce OMRI[2] was an Italian race car driver and entrepreneur, the founder of the Scuderia Ferrari Grand Prix motor racing team, and subsequently of the Ferrari car manufacturer. He was often referred to as "il Commendatore"

Born in Modena, Enzo Ferrari grew up with little formal education but a strong desire to race cars. During World War I he was assigned to the third Alpine Artillery division of the Italian Army. His father Alfredo, as well as his older brother, also named Alfredo, died in 1916 as a result of a widespread Italian flu outbreak. Ferrari became severely ill himself in the 1918 flu pandemic and was consequently discharged from Italian service. Upon returning home he found that the family firm had collapsed.

Having no other job prospects, Ferrari eventually settled for a job at a smaller car company called CMN (Costruzioni Meccaniche Nazionali), redesigning used truck bodies into small passenger cars. He took up racing in 1919 on the CMN team, but had little initial success.

He left CMN in 1920 to work at Alfa Romeo and racing their cars in local races he had more success. In 1923, racing in Ravenna, he acquired the Prancing Horse badge which decorated the fuselage of Francesco Baracca's (Italy's leading ace of WWI) SPAD S.XIII fighter, given from his mother, taken from the wreckage of the plane after his mysterious death. This icon would have to wait until 1932 to be displayed on a racing car. It is interesting to note that the Ferrari emblem matches that of the city of Stuttgart and is identical to the center of the Porsche emblem.

In 1924 Ferrari won the Coppa Acerbo at Pescara. His successes in local races encouraged Alfa to offer him a chance of much more prestigious competition. Ferrari turned this opportunity down and did not race again until 1927. He continued to work directly for Alfa Romeo until 1929 before starting Scuderia Ferrari as the racing team for Alfa.

Ferrari managed the development of the factory Alfa cars, and built up a team of over forty drivers, including Giuseppe Campari and Tazio Nuvolari. Ferrari himself continued racing until 1932.

The support of Alfa Romeo lasted until 1933, when financial constraints made Alfa withdraw. Only at the intervention of Pirelli did Ferrari receive any cars at all. Despite the quality of the Scuderia drivers, the company won few victories (1935 in Germany by Nuvolari was a notable exception). Auto Union and Mercedes dominated the era.

In 1937 Alfa took control of its racing efforts again and again, reducing Ferrari to Director of Sports under Alfa's engineering director. Ferrari soon left, but a contract clause restricted him from racing or designing for four years.

In response, Ferrari organized Auto-Avio Costruzioni, a company supplying parts to other racing teams. Ferrari did manage to manufacture two cars for the 1940 [Mille Miglia]], driven by Alberto Ascari and Lotario Rangoni. During World War II his firm was involved in war production for Mussolini's fascist government. Following Allied bombing of the factory, Ferrari relocated from Modena to Maranello. It was not until after World War II that Ferrari sought to shed his fascist reputation and make cars bearing his name, founding today's Ferrari S.p.A. in 1947.

The first open-wheel race was in Turin in 1948 and the first victory came later in the year in Lago di Garda. Ferrari participated in the Formula 1 World Championship since its introduction in 1950 but the first victory was not until the British Grand Prix of 1951. The first championship came in 1952–53, when the Formula One season was raced with Formula Two cars. The company also sold production sports cars in order to finance the racing endeavours not only in Grands Prix but also in events such as the Mille Miglia and Le Mans.

Ferrari's decision to continue racing in the Mille Miglia, a dangerous and grueling long-distance competition over mostly unpaved roads, brought the company new victories and greatly increased public recognition. However, increasing speeds, poor roads, and nonexistent crowd protection eventually spelled disaster for both the race and Ferrari. During the 1957 Mille Miglia, near the town of Guidizzolo, a 4.0-litre Ferrari 335S driven by the flamboyant Alfonso de Portago was traveling at 250 km/h when it blew a tire and crashed into the roadside crowd, killing de Portago, his co-driver, and nine spectators, including five children. In response, Enzo Ferrari and Englebert, the tyre manufacturer were charged with manslaughter in a lengthy criminal prosecution that was finally dismissed in 1961. It was later concluded that team's decision to continue racing de Portago's car[3] for an extra stage rather than stop for a tyre change caused the accident. The tragedy led to the decision of some racing competitors, such as Maserati, to leave racing competition entirely.

Many of the firm's greatest victories came at Le Mans (14 victories, including six in a row 1960–65) rather than in Grand Prix. Certainly the company was more involved there than in Formula One during the 1950s and 1960s despite the successes of Juan-Manuel Fangio (1956), Mike Hawthorn (1958), Phil Hill (1961) and John Surtees (1964).

In the 1960s the problems of reduced demand and inadequate financing forced Ferrari to allow Fiat to take a stake in the company. Ferrari had offered Ford the opportunity to buy the firm in 1963 for US$18 million but, late in negotiations, Ferrari withdrew. This decision triggered Ford's decision to launch a serious European sports car racing program, which resulted into the Ford GT40. The company became joint-stock and Fiat took a small share in 1965 and then in 1969 they increased their holding to 50% of the company. (In 1988 Fiat's holding rose to 90%).

Ferrari remained managing director until 1971. Despite stepping down he remained an influence over the firm until his death. The input of Fiat took some time to have effect. It was not until 1975 with Niki Lauda the firm won any championships — the skill of the driver and the ability of the engine overcoming the deficiencies of the chassis and aerodynamics. After those successes and the promise of Jody Scheckter's title in 1979, the company's Formula One championship hopes fell into the doldrums.

1982 opened with a strong car, the 126C2, world-class drivers, and promising results in the early races. However, Gilles Villeneuve was killed in the 126C2 in May, and teammate Didier Pironi had his career cut short in a violent end over end flip on the misty back straight at Hockenheim in August. Pironi was leading the driver's championship at the time; he would lose the lead as he sat out the remaining races. The team would not see championship glory again during Ferrari's lifetime.

Ferrari's management style was autocratic and he was known to pit driver against driver in the hope of improving performance. He did not often get close to his drivers.[4]

Enzo Ferrari was married to Laura Dominica Garello Ferrari (c. 1900 - 1978) from 1932 until her death.[6] They had one son, Alfredo "Dino", who was born in 1932 and groomed as Enzo's successor, but he suffered from ill-health and died from muscular dystrophy in 1956.[7] Enzo had a second son, Piero, with his mistress Lina Lardi in 1945. Piero was recognized as Enzo's son after Laura's death, and is currently a vice-president of the Ferrari company with a 10% share ownership.[8]

After the death of Luigi Musso, Ferrari avidly pursued a relationship with Musso's girlfriend Fiamma Breschi. “I said I couldn’t marry him,” Breschi stated, “first of all because I was still in love (with Musso), and secondly because of the age difference.” After a long period of correspondence, Breschi agreed to become his mistress, and Ferrari arranged a house and small shop for her near Modena. Breschi frequently attended team races and regularly reported to Ferrari on personnel and equipment issues she had observed.

Enzo Ferrari spent a reserved life, and rarely granted interviews.

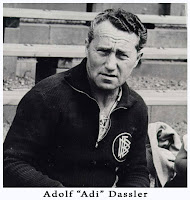

Adolf "Adi" Dassler (ADIDAS)

Adolf "Adi" Dassler (born 5 November 1900 in Herzogenaurach, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire; died 6 September 1978 in Herzogenaurach, West Germany) was the founder of the German sportswear company Adidas.

Trained as a cobbler, Adi Dassler started to produce his own sports shoes in his mother's laundry after his return from World War I. His father, Christoph, who worked in a shoe factory, and the Zehlein brothers, who produced the handmade spikes for track shoes in their blacksmith's shop, supported Dassler in starting his own business. On July 1, 1924, his older brother Rudolf Dassler joined the business, which became the Gebrüder Dassler Schuhfabrik (Dassler Brothers Shoe Factory).

At the 1928 Olympics, Dassler equipped several athletes, laying the foundation for the international expansion of the company. During the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Dassler equipped Jesse Owens of the USA with his shoes. Jesse Owens won 4 gold medals in the year he wore Adi's shoes.

With the rise of Adolf Hitler in the 1930s, both Dassler brothers joined the Nazi Party, with Rudolf reputed as being the more ardent National Socialist.[1] Rudolf was drafted, and later captured, while Adi stayed behind to produce boots for the Wehrmacht.[2] The war exacerbated the differences between the brothers and their wives. Rudolf, upon his capture by American troops, was suspected of being a member of the SS, information supposedly supplied by none other than his brother Adi.[3]

By 1948, the rift between the brothers widened. Rudolf left the company to found Puma on the other side of town (across the Aurach River), and Adolf Dassler renamed the company Adidas after his own nickname (Adi Dassler).

In 1973, Adolf Dassler's son Horst Dassler founded Arena, a producer of swimming equipment. After Adolf Dassler's death in 1978, Horst and his wife Käthe took over the management. Horst died nine years later, in 1987. Adidas was transformed into a private limited company in 1989, but remained family property until its IPO in 1995.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)